The math is pretty basic. How many satellites are going to go up over the next decade? How many solar panels will they need? And how many are being manufactured that fit the bill? Turns out the answers are: a lot, a hell of a lot and not nearly enough. That’s where Regher Solar aims to make its mark, by bringing the cost of space-quality solar panels down by 90% while making an order of magnitude more of them.

It’s not exactly a modest goal, but fortunately the science and market seem to be in favor, giving the company something of a tailwind. The question is finding the right balance between cost and performance while remaining relatively easy to manufacture. Of course, if there was an easy answer there, someone would already be doing that.

Solar cells for use on the planet’s surface are very different from the ones being used in space. Because down here there are few size and mass limitations; you can make the cells bigger, heavier and less efficient — and much cheaper. Space solar cells, on the other hand, need to be highly efficient, extremely light and resistant to the various dangers of space, such as radiation and temperature fluctuation: a top-tier product that costs five-10 times as much and uses small-scale processes and expensive materials.

Regher Solar has created a space-grade solar cell that, while it doesn’t reach those dedicated space solar levels, isn’t that far off — yet costs a fraction as much and can be made at scale with existing processes. If you’re making a single $200 million geostationary satellite, you don’t mind paying for the best panels out there, since it’s only a small part of the overall cost. But if you’re looking to deploy 10,000 small satellites with short lifespans, panels start making up a lot more of your bill of materials, and a 20% performance hit doesn’t sound so bad.

Stanislau Herasimenka, CEO and co-founder of Regher, explained that there’s no magic bullet to their product, but rather a lot of incremental improvements and an understanding of what’s actually important to the new space economy.

“The tech has evolved in a high-cost, low-volume space,” he explained. “Space panels, they start from a very expensive substrate, usually germanium or gallium arsenide, and lots of expensive processing. Then there’s space-grade interconnect, an expensive glass and carbon fiber or aluminum substrate, manual assembly… top performance and low degradation, but it’s totally not scalable. If they wanted 10 times more of these, they just couldn’t do it.”

Yet we’re clearly on our way to doubling, tripling and eventually 10X-ing the number of satellites being launched. They can’t just slap terrestrial cells on there — they’d quickly fail — and the tried-and-true makers of fancy III-V cells won’t have nearly enough stock. So Regher took the best of both worlds to make their cells space-ready, but cheap and able to be made in a hurry.

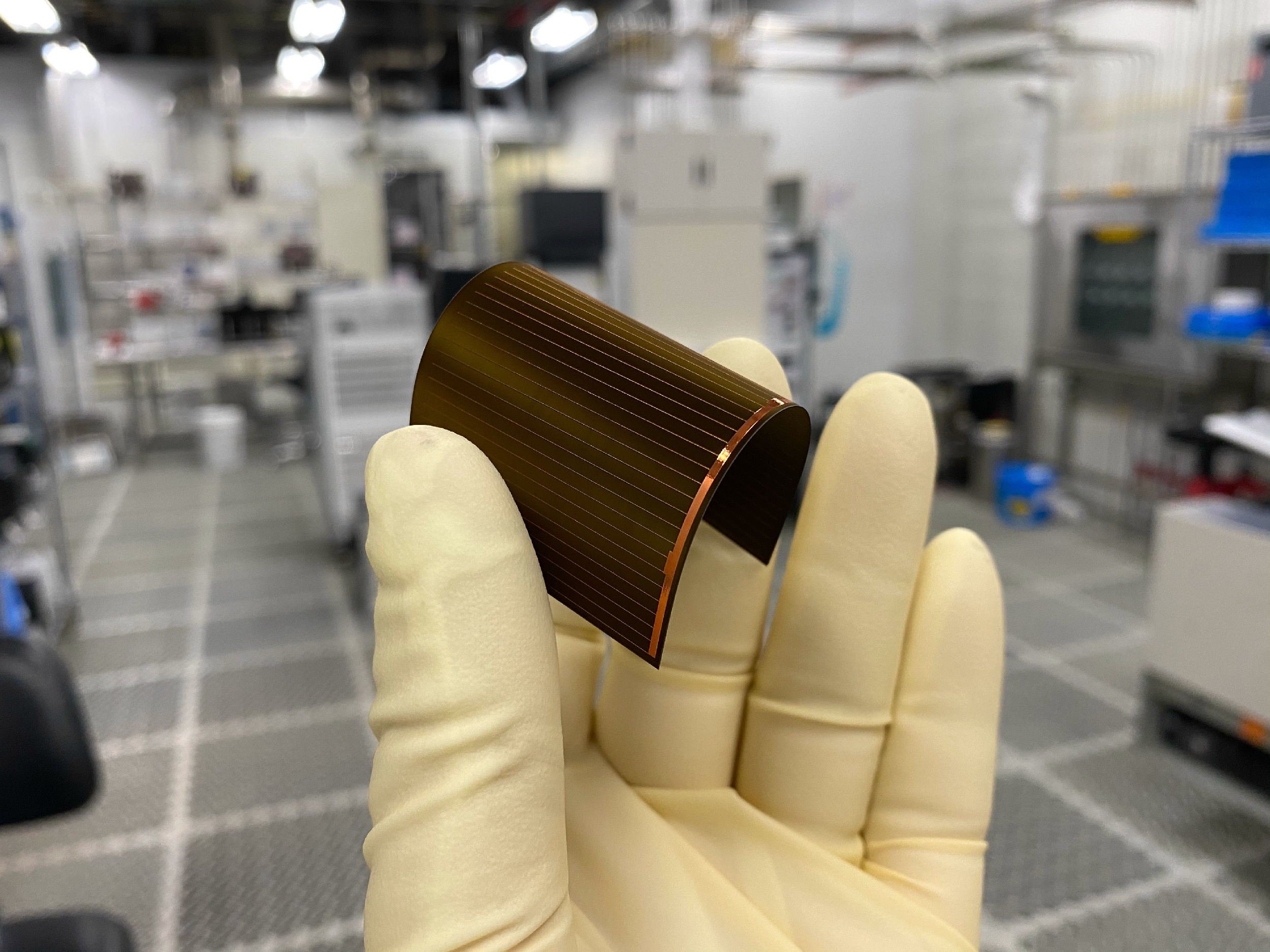

A Regher flexible silicon solar cell made with a 20-micron silicon substrate. Image Credits: Regher Solar

“Right now we’re running an R&D pilot line where we can make small quantities of panels — 50 kilowatts, about 5% of what the space industry does,” he said. “But because we designed with silicon, and the package to be compatible with automated production, we should be able to transition from pilot to 10 megawatts, which is 10 times more than what the space industry does, in a year.”

Although the product is new, it doesn’t use any exotic or unprecedented techniques, so ramping up like that really may be possible. Herasimenka described a few of the changes they made to achieve space-like performance at terrestrial-like prices.

In the first place they took the thickness of the silicon substrate way down, meaning it’s paradoxically much more resistant to radiation, since it will absorb less. They also changed the impurities and doping in it so that it cures at a low temperature, allowing what damage is caused to be fixed by simply being heated to 80 degrees Celsius. The coating, interconnect and bonding are space-stable. There’s also less space dedicated to what you might call the bezel, letting the sun-sensitive cells make up more of the surface area. The plan is also to make them flexible (as demonstrated in the images here), to better fit unusual shapes and to increase physical hardiness.

Knowing how far to go depended on the moving target that is the cost and planned life of a given constellation-bound satellite. It’s counterintuitive, but it can be a hazard to a constellation company like Starlink if their satellites perform too well. With thousands of satellites, unit economics come into play — and you don’t want them to be any better or more expensive than they have to be if the stated plan is to replace them five years from launch. If they’re still going at 100% then, you probably could have saved a lot of money somewhere along the line.

“Constellation designers design for a particular period of time in a particular orbit,” Herasimenka said. “Nobody wants to live for two weeks, and nobody wants 15 years; mostly they go to low Earth orbit and only live there for five-seven years. So we designed for this exact requirement. If they degrade after that, we don’t care because our customer doesn’t care.”

Regher taking its shot at this emerging market earned it a spot in Techstars’ 2019 batch, after which they started talking to manufacturers and roughing out deals. They also snagged a NASA SBIR Phase I award and an NSF Phase II, totaling $1.1 million. With prototypes and some validating funding in hand, they collected $33 million in LOIs over the summer and have $50 million more being hammered out, Herasimenka said.

As promising as that is, the company needs to move fast or risk others moving in and eating their lunch. “Everything can change in just a few years, and by the time an industry realizes it, the market opportunity is gone,” he said. Clearly Regher Solar intends to be the one to snatch up that opportunity, but they are now looking for significant investment to bring first their pilot, then later the full scale manufacturing lines up to speed. They’re not ready to announce the specifics, but Herasimenka said they are raising a $5 million institutional equity seed round that should close before the end of the year, plus $900,000 from individuals.

With interest from established aerospace companies and stamps of approval (via SBIR) of both NASA and the NSF, Regher seems well positioned to make its play. Whether the hard part is designing the new panel or actually making it, though? They’re about to find out.